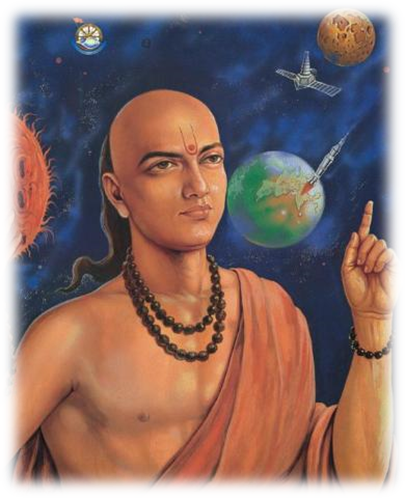

# bhaskaracharya 2

भास्कराचार्य व्दीतीय

भारतीय खगोलविज्ञान आणि गणित यांची परंपरा आर्यभट (पाचवं शतक) याच्यापासून सुरू होऊन भास्कराचार्य द्वितीय (1114-1185) याच्यापर्यंत पोचली. अबाधित परंपरा पोसणाऱ्या या काल खंडाला भारतातलं सुवर्णयुग म्हटलं, तर अतिशयोक्ती होणार नाही. जवळपासच्या शेजारी देशांच्या किंवा सुदूर पश्चिमेतल्या युरोपच्या तुलनेत भारत हा गणित आणि विज्ञान यांच्या अभ्यासात तेव्हा नक्कीच अग्रेसर होता. भारतातल्या विद्वानांनी लिहिलेल्या पुस्तकांचे अनुवाद अरबस्तानातल्या उत्साही अभ्यासकांनी प्रसिद्ध केल्यानं भारतीय ज्ञान इतरत्र माहीत झालं.

अशा या विद्वानमाळेतले काही चमकदार मणी होते ः आर्यभट (1)- लटदेव- ब्रह्मगुप्त- भास्कर (1) - लल्ला-आर्यभट (2) -श्रीपती-भास्कर (2).

या माळेतला शेवटचा मणी म्हणजे भास्कर (2) किंवा ज्याला आपण भास्कराचार्य या नावानं ओळखतो तो! भास्कराचार्याच्या पश्चात भारतात मुख्यत्वेकरून केरळात गणिती संशोधन होत राहिलं; पण अगदी अलीकडच्या काळापर्यंत त्या शोधांचं महत्त्व पूर्णपणे माहीत झालेलं नव्हतं. जानेवारी 2014 मध्ये आयोजित भास्कराचार्याच्या 900 व्या जयंती समारंभानिमित्त त्याच्या कार्याची थोडक्यात माहिती देण्याचा हा प्रयत्न आहे.

भास्कराचं जन्मस्थान जळगाव जिल्ह्यात चाळीसगावच्या नैर्ऋत्येला पाटणगावी असावं (पण याबाबतीत तज्ज्ञांत एकमत नाही).

भास्कराचा मोठा ग्रंथ "सिद्धान्तशिरोमणी' हा चार भागांत आहे; परंतु प्रत्येक भाग हाही एक स्वतंत्र ग्रंथच म्हणता येईल. त्या चार भागांची नावं ः 1) लीलावती (पाटी गणित), 2) बीजगणित, 3) ग्रहगणिताध्याय आणि 4) गोलाध्याय.

"ग्रहगणिताध्याय' या खंडात 4 हजार 346 श्लोक असून, त्यांत ग्रहांसंबंधीचं व पंचांगाचं गणित आहे. सूर्य ज्या क्रांतिवृत्तावरून भ्रमण करतो, त्यात आणि विषुववृत्तामध्ये 23।। आसांचा कोन असल्यामुळं भाष्य आणि स्पष्ट सूर्योदयात अंतर पडतं. त्याचं गणित गोलीय त्रिकोणमिती वापरून भास्कराचार्यानं "उदयांतर संस्कार' या मार्गानं सोडवलं.

"ग्रहगणिताध्याया'चं अधिक स्पष्टीकरण करण्यासाठी त्यानं "गोलाध्याय' हा चौथा ग्रंथ लिहिला. त्यात 2 हजार 100 श्लोक आहेत. या ग्रंथाचा पुष्कळ प्रचार झाला आणि अनुवादांमुळं वेगवेगळ्या देशांत तो माहीत झाला आणि वापरात आला. भास्कराचार्य खगोलविज्ञानातल्या कामगिरीबद्दल प्रसिद्ध आहे व ती कामगिरी "गोलाध्याय' वाचल्यावर किती महत्त्वाची होती, ते ध्यानात येतं.

"ग्रहगणिताध्याया'च्या सुरवातीलाच भास्कराचार्यानं आपली विनोदबुद्धी दाखवली आहे. तो म्हणतो ः ""विद्वान वाचक या पुस्तकातल्या बुद्धिवर्धक चमत्कारांनी संतुष्ट होतील, तर दुर्जन लोकांना विषय न समजल्यामुळं तो हास्यापद वाटेल. अशा तऱ्हेनं विद्वान आणि मूर्ख अशा दोघांनाही हा विषय मनोरंजक वाटेल.''

भास्कराचार्यानं "गोलाध्याय' या ग्रंथाच्या सुरवातीलाच गणित आणि खगोलशास्त्र यांचं एकत्र येणं का महत्त्वाचं आहे, याची चर्चा केली आहे. त्यानं आवर्जून म्हटलं आहे, की खगोलाची माहिती गणिताद्वारे मिळते आणि अशा माहितीशिवाय गणित हा एक नीरस विषय असेल. त्याचप्रमाणे जर खगोल-अभ्यासकाला गणित येत नसेल, तर तो एक "मूर्ख' म्हणून ओळखला जाईल.

अशा प्रस्तावनेतून भास्करानं आपल्या चर्चेला सुरवात केली आहे. सुरवातीलाच त्यानं "पृथ्वी गोल असून दक्षिण गोलार्धातली माणसं आपल्या विरुद्ध दिशेनं (वर-खाली) उभी असतात,' हे सांगितलं आहे. खुद्द पृथ्वीला गुंडाळणारे तिच्याभोवती वायूचे सात गोलाकार स्तर असतात. त्या सात स्तरांची नावं ः 1) भूवायुगोल, 2) प्रवह, 3) उद्वहसंज्ञक, 4) संवहसंज्ञक, 5) सुवहसंज्ञक, 6) परिवहसंज्ञक, 7) परावहसंज्ञक.

आधुनिक माहितीप्रमाणे पृथ्वीच्या वायुमंडलाचे विविध स्तर निश्चित केले जातात. अर्थात भास्करानं वरील माहिती कशाच्या बळावर मिळवली, त्याची चर्चा केलेली नाही; तसंच (बहुतेक पुराणांतल्या वर्णनांवरून) त्यानं असा निष्कर्ष काढला, की जमिनीपासून सुमारे 100 किलोमीटर उंचीवर पाण्याचे ढग, विजा, इंद्रधनुष्य, गंधर्वनगरी आणि विविध चित्रविचित्र गोष्टी सापडतात.

पण या प्राथमिक चर्चेतून एक गोष्ट स्पष्ट होते. मुळात पृथ्वी, इतर ग्रह, सूर्य आदी आकाशात भ्रमण करणाऱ्या गोष्टी स्वतःच्या दिमतीवर टिकून आहेत. उदाहरणार्थ ः पृथ्वी! पूर्वीच्या विचारांप्रमाणे जर पृथ्वी चार दिग्गजांवर ठेवलेली आहे, असं मानलं तर ते हत्ती कशावर उभे आहेत? हत्तीच्या खाली कासव, तर कासवाच्या खाली काय? अशा तऱ्हेच्या तर्कात अडकण्याऐवजी भास्करानं वेगळाच मार्ग निवडलाय.

पण या प्राथमिक चर्चेतून एक गोष्ट स्पष्ट होते. मुळात पृथ्वी, इतर ग्रह, सूर्य आदी आकाशात भ्रमण करणाऱ्या गोष्टी स्वतःच्या दिमतीवर टिकून आहेत. उदाहरणार्थ ः पृथ्वी! पूर्वीच्या विचारांप्रमाणे जर पृथ्वी चार दिग्गजांवर ठेवलेली आहे, असं मानलं तर ते हत्ती कशावर उभे आहेत? हत्तीच्या खाली कासव, तर कासवाच्या खाली काय? अशा तऱ्हेच्या तर्कात अडकण्याऐवजी भास्करानं वेगळाच मार्ग निवडलाय.

त्या काळच्या बौद्ध तत्त्वज्ञानानुसार, पृथ्वी आकाशात सतत "खाली' पडत असते, असं मानलं जाई. या मताचं खंडन करून, "पृथ्वी आकाशात एका जागी स्थिर आहे,' असं प्रतिपादन करताना भास्करानं, पृथ्वीवर पडणाऱ्या एखाद्या दगडाचं उदाहरण दिलं आहे. दगड "खाली' पडण्याच्या वेगापेक्षा पृथ्वी खाली पडण्याचा वेग बराच जास्त असल्यानं तो दगड पृथ्वीतलापर्यंत पोचेल कसा, हा प्रश्न भास्कराचार्यानं उपस्थित केला. त्याच्या मते, पृथ्वी दगडाला आकर्षित करते, त्यामुळं दगड पृथ्वीवर पडतो; पण पृथ्वी स्वतः आपल्याजागी स्थिर असते.

यासंदर्भात गुरुत्वाकर्षणाच्या सिद्धान्ताच्या जनकत्वाचं श्रेय भास्कराचार्याला द्यावं, असा एक मतप्रवाह आहे. त्याची इथं थोडक्यात दखल घेऊ. न्यूटननं सफरचंद पडलं म्हणून पृथ्वीच्या गुरुत्वाकर्षणाचा निष्कर्ष काढला, तसाच निष्कर्ष इथं भास्करानं काढलेला नाही काय, इथपर्यंत आपण दोन्ही उदाहरणं एका पातळीची मानू शकतो; पण न्यूटनला वास्तविक गुरुत्वाकर्षणाचा व्यस्तवर्गाचा नियम गवसला, तो केप्लरच्या ग्रहगतीच्या नियमांचं गणिती विश्लेषण करून. त्यासाठी त्यानं स्वतःच शोधलेल्या कलनशास्त्र (कॅल्क्युलस) या नव्या गणिती शाखेचा उपयोग केला; म्हणून गुरुत्वाकर्षणाच्या नियमाचं श्रेय न्यूटनला दिलं जातं, ते योग्यच आहे. अशा तऱ्हेचं गणिती विवेचन भास्कराच्या किंवा इतर कुणाच्या भारतीय विचारकाच्या ग्रंथात सापडत नाही.

मात्र, "गोलाध्याया'चा प्रमुख भर आकाशातल्या ग्रह-ताऱ्यांच्या निरीक्षणासाठी वापरलेल्या गणितावर आहे. अमुक अक्षांश-रेखांश असलेल्या जागेतून अमुक वेळी निरीक्षण केल्यास तमुक ग्रह किंवा तारा कुठं सापडेल, अशा तऱ्हेचे प्रश्न इथं सोडवले आहेत. त्यासाठी भूमिती आणि गोलीय त्रिकोणमिती वापरली आहे. हा विषय कॅल्क्युलसपेक्षा जुना आणि म्हणून बहुतेक गणिती बहाद्दरांना परिचित होता.

त्या काळात पुस्तकं श्लोकबद्ध संस्कृतात लिहिली जात. अशा स्थितीत चित्रांशिवाय लिहिलेलं वर्णन समजणं सोपं नव्हतं; म्हणून "टीकां'च्या माध्यमातून लेखक स्वतः (किंवा अन्य टीकाकार) श्लोकांचं विवेचन करत. अशा टीकेत आधुनिक गणितात वापरतात, तशा आकृत्या आणि उदाहरणं वापरून लेखनाचा अर्थ विशद केला जात असे. "गोलाध्याया'तसुद्धा ही पद्धत दिसते.

"गोलाध्याय'मधलं एक प्रकरण सर्वस्वी यंत्रांना, म्हणजे निरीक्षणाच्या उपकरणांना, वाहिलेलं आहे. त्यात काल मोजणारी उपकरणं आहेत. चक्रयंत्र, अर्धचापयंत्र, तुरीययंत्र, फलकयंत्र, यष्टियंत्र आदींची चर्चा पाहून भास्कराचार्य प्रत्यक्ष निरीक्षणांनादेखील महत्त्व देत असे, याची जाणीव होते. ही यंत्रं कशी बनवायची आणि कशी वापरायची, याची चर्चा या प्रकरणात आढळते.

"ग्रहणवासना' या अध्यायात ग्रहणांची चर्चा करताना सूर्यग्रहण आणि चंद्रग्रहण यांच्या स्पर्शदिशा आणि मोक्षदिशा कुठं असतात आणि का असतात, यांची कारणमीमांसा करण्यात आली आहे. सूर्यग्रहणात पश्चिम दिशेत स्पर्श तर पूर्वेत मोक्ष होतो, तर चंद्रग्रहणात याच्या उलट स्थिती असते. याची चर्चा करताना भास्कराचार्य राहू-केतूची संकल्पना खोडून काढतो; पण वेद-पुराण आदींमधल्या विश्वासांना तडा जाऊ नये म्हणून आपला निष्कर्ष अनाक्रमक शब्दांत व्यक्त करतो!

सूर्य ज्या मार्गानं जातो, ते क्रांतिवृत्त आणि त्यानं विषुववृत्ताशी केलेला कोन यांचा एक परिणाम म्हणजे दिवस आणि रात्र यांच्या कालखंडात फरक पडतो. त्यामुळं सूर्य विषुववृत्ताच्या उत्तरेला असला तर उत्तर गोलार्धात रात्रीपेक्षा दिवस लांब, तर दक्षिण गोलार्धात

त्याउलट स्थिती असते. त्रिकोणमितीनं या गोष्टीचा उलगडा होऊ शकतो, हे भास्कराचार्यानं दाखवून दिलं आहे.

याचाच परिणाम म्हणून 66 अंश अक्षांशाच्या उत्तरेला काही काळ मध्यरात्री आकाशात सूर्य दिसतो (उन्हाळी महिन्यात), तर असाही काळ असतो, की जेव्हा दिवस सूर्यदर्शनाशिवाय जातो (थंडीच्या मोसमात). याचं कारणही वरील गणिताद्वारे देता येतं, हे भास्कराचार्य समजावून सांगतो. भास्कराचा पिंड शिक्षकाचा आहे, याची जाणीव "गोलाध्याय' वाचताना पदोपदी होते. कारण, ठिकठिकाणी त्यानं प्रश्न पेरले आहेत व उत्तरं दिली आहेत. शेवटचा "प्रश्नाध्याय' तर प्रश्नांनीच व्यापलेला आहे. मला वाटतं, की त्याची ही पद्धत आधुनिक गणित आणि विज्ञान यांना वाहिलेल्या पाठ्यपुस्तकांनी वापरण्याजोगी आहे.

भास्कराचार्याचं गणितावरचं कार्यही प्रगल्भ आहे. "लीलावती' या ग्रंथात भूमिती, बीजगणित व अंकगणिताचा सुंदर संगम दिसतो. अशा विषयांवर आधारित गणितं मनोरंजक आहेत.

एक उदाहरण पाहा ः मधमाश्यांच्या समूहाच्या निम्म्या संख्येच्या वर्गमुळाइतक्या संख्येनं एक थवा मालती वृक्षाकडं गेला. त्यांच्या पाठोपाठ एकूण संख्येच्या आठ नवमांश माशाही तिकडं गेल्या. एक नरमाशी कमळाच्या बंद पाकळ्यांत अडकून पडली, तर फुलाबाहेर तिची जोडीदार तिच्या आवाजाला प्रतिसाद देत उडत होती...तर मुली, सांग एकंदर किती माश्या होत्या?

(भास्करानं हा ग्रंथ गणितात हुशार असलेल्या आपल्या कन्येला - लीलावती हिला - उद्देशून लिहिला होता, असा एक समज आहे).

भास्करानं अनेक गणिती शोध लावले. चक्रवाल पद्धत वापरून त्यानं विशिष्ट प्रकारची गणिती समीकरणं सोडवून दाखवली. उदाहरणार्थ ः 61x2 + 1 = y2 हे पूर्णांक x, y साठी कसे सोडवणार, हा प्रश्न 1657 मध्ये फर्मा नावाच्या फ्रेंच गणितज्ञानं उपस्थित केला होता. अनेकांनी प्रयत्न केले आणि अखेर 1732 मध्ये ऑयलर या प्रख्यात गणितज्ञानं तो सोडवला; पण अलीकडं असं लक्षात आलं आहे, की हा प्रश्न भास्कराचार्यानं 1150 मध्येच सोडवला होता! चक्रवाल पद्धत वापरून त्यानं काढलेलं उत्तर ः

x = 226153980, y = 1766319049

या उदाहरणातून भास्कराच्या कर्तृत्वाची कल्पना येते.

या माळेतला शेवटचा मणी म्हणजे भास्कर (2) किंवा ज्याला आपण भास्कराचार्य या नावानं ओळखतो तो! भास्कराचार्याच्या पश्चात भारतात मुख्यत्वेकरून केरळात गणिती संशोधन होत राहिलं; पण अगदी अलीकडच्या काळापर्यंत त्या शोधांचं महत्त्व पूर्णपणे माहीत झालेलं नव्हतं. जानेवारी 2014 मध्ये आयोजित भास्कराचार्याच्या 900 व्या जयंती समारंभानिमित्त त्याच्या कार्याची थोडक्यात माहिती देण्याचा हा प्रयत्न आहे.

भास्कराचं जन्मस्थान जळगाव जिल्ह्यात चाळीसगावच्या नैर्ऋत्येला पाटणगावी असावं (पण याबाबतीत तज्ज्ञांत एकमत नाही).

भास्कराचा मोठा ग्रंथ "सिद्धान्तशिरोमणी' हा चार भागांत आहे; परंतु प्रत्येक भाग हाही एक स्वतंत्र ग्रंथच म्हणता येईल. त्या चार भागांची नावं ः 1) लीलावती (पाटी गणित), 2) बीजगणित, 3) ग्रहगणिताध्याय आणि 4) गोलाध्याय.

"ग्रहगणिताध्याय' या खंडात 4 हजार 346 श्लोक असून, त्यांत ग्रहांसंबंधीचं व पंचांगाचं गणित आहे. सूर्य ज्या क्रांतिवृत्तावरून भ्रमण करतो, त्यात आणि विषुववृत्तामध्ये 23।। आसांचा कोन असल्यामुळं भाष्य आणि स्पष्ट सूर्योदयात अंतर पडतं. त्याचं गणित गोलीय त्रिकोणमिती वापरून भास्कराचार्यानं "उदयांतर संस्कार' या मार्गानं सोडवलं.

"ग्रहगणिताध्याया'चं अधिक स्पष्टीकरण करण्यासाठी त्यानं "गोलाध्याय' हा चौथा ग्रंथ लिहिला. त्यात 2 हजार 100 श्लोक आहेत. या ग्रंथाचा पुष्कळ प्रचार झाला आणि अनुवादांमुळं वेगवेगळ्या देशांत तो माहीत झाला आणि वापरात आला. भास्कराचार्य खगोलविज्ञानातल्या कामगिरीबद्दल प्रसिद्ध आहे व ती कामगिरी "गोलाध्याय' वाचल्यावर किती महत्त्वाची होती, ते ध्यानात येतं.

"ग्रहगणिताध्याया'च्या सुरवातीलाच भास्कराचार्यानं आपली विनोदबुद्धी दाखवली आहे. तो म्हणतो ः ""विद्वान वाचक या पुस्तकातल्या बुद्धिवर्धक चमत्कारांनी संतुष्ट होतील, तर दुर्जन लोकांना विषय न समजल्यामुळं तो हास्यापद वाटेल. अशा तऱ्हेनं विद्वान आणि मूर्ख अशा दोघांनाही हा विषय मनोरंजक वाटेल.''

भास्कराचार्यानं "गोलाध्याय' या ग्रंथाच्या सुरवातीलाच गणित आणि खगोलशास्त्र यांचं एकत्र येणं का महत्त्वाचं आहे, याची चर्चा केली आहे. त्यानं आवर्जून म्हटलं आहे, की खगोलाची माहिती गणिताद्वारे मिळते आणि अशा माहितीशिवाय गणित हा एक नीरस विषय असेल. त्याचप्रमाणे जर खगोल-अभ्यासकाला गणित येत नसेल, तर तो एक "मूर्ख' म्हणून ओळखला जाईल.

अशा प्रस्तावनेतून भास्करानं आपल्या चर्चेला सुरवात केली आहे. सुरवातीलाच त्यानं "पृथ्वी गोल असून दक्षिण गोलार्धातली माणसं आपल्या विरुद्ध दिशेनं (वर-खाली) उभी असतात,' हे सांगितलं आहे. खुद्द पृथ्वीला गुंडाळणारे तिच्याभोवती वायूचे सात गोलाकार स्तर असतात. त्या सात स्तरांची नावं ः 1) भूवायुगोल, 2) प्रवह, 3) उद्वहसंज्ञक, 4) संवहसंज्ञक, 5) सुवहसंज्ञक, 6) परिवहसंज्ञक, 7) परावहसंज्ञक.

आधुनिक माहितीप्रमाणे पृथ्वीच्या वायुमंडलाचे विविध स्तर निश्चित केले जातात. अर्थात भास्करानं वरील माहिती कशाच्या बळावर मिळवली, त्याची चर्चा केलेली नाही; तसंच (बहुतेक पुराणांतल्या वर्णनांवरून) त्यानं असा निष्कर्ष काढला, की जमिनीपासून सुमारे 100 किलोमीटर उंचीवर पाण्याचे ढग, विजा, इंद्रधनुष्य, गंधर्वनगरी आणि विविध चित्रविचित्र गोष्टी सापडतात.

त्या काळच्या बौद्ध तत्त्वज्ञानानुसार, पृथ्वी आकाशात सतत "खाली' पडत असते, असं मानलं जाई. या मताचं खंडन करून, "पृथ्वी आकाशात एका जागी स्थिर आहे,' असं प्रतिपादन करताना भास्करानं, पृथ्वीवर पडणाऱ्या एखाद्या दगडाचं उदाहरण दिलं आहे. दगड "खाली' पडण्याच्या वेगापेक्षा पृथ्वी खाली पडण्याचा वेग बराच जास्त असल्यानं तो दगड पृथ्वीतलापर्यंत पोचेल कसा, हा प्रश्न भास्कराचार्यानं उपस्थित केला. त्याच्या मते, पृथ्वी दगडाला आकर्षित करते, त्यामुळं दगड पृथ्वीवर पडतो; पण पृथ्वी स्वतः आपल्याजागी स्थिर असते.

यासंदर्भात गुरुत्वाकर्षणाच्या सिद्धान्ताच्या जनकत्वाचं श्रेय भास्कराचार्याला द्यावं, असा एक मतप्रवाह आहे. त्याची इथं थोडक्यात दखल घेऊ. न्यूटननं सफरचंद पडलं म्हणून पृथ्वीच्या गुरुत्वाकर्षणाचा निष्कर्ष काढला, तसाच निष्कर्ष इथं भास्करानं काढलेला नाही काय, इथपर्यंत आपण दोन्ही उदाहरणं एका पातळीची मानू शकतो; पण न्यूटनला वास्तविक गुरुत्वाकर्षणाचा व्यस्तवर्गाचा नियम गवसला, तो केप्लरच्या ग्रहगतीच्या नियमांचं गणिती विश्लेषण करून. त्यासाठी त्यानं स्वतःच शोधलेल्या कलनशास्त्र (कॅल्क्युलस) या नव्या गणिती शाखेचा उपयोग केला; म्हणून गुरुत्वाकर्षणाच्या नियमाचं श्रेय न्यूटनला दिलं जातं, ते योग्यच आहे. अशा तऱ्हेचं गणिती विवेचन भास्कराच्या किंवा इतर कुणाच्या भारतीय विचारकाच्या ग्रंथात सापडत नाही.

मात्र, "गोलाध्याया'चा प्रमुख भर आकाशातल्या ग्रह-ताऱ्यांच्या निरीक्षणासाठी वापरलेल्या गणितावर आहे. अमुक अक्षांश-रेखांश असलेल्या जागेतून अमुक वेळी निरीक्षण केल्यास तमुक ग्रह किंवा तारा कुठं सापडेल, अशा तऱ्हेचे प्रश्न इथं सोडवले आहेत. त्यासाठी भूमिती आणि गोलीय त्रिकोणमिती वापरली आहे. हा विषय कॅल्क्युलसपेक्षा जुना आणि म्हणून बहुतेक गणिती बहाद्दरांना परिचित होता.

त्या काळात पुस्तकं श्लोकबद्ध संस्कृतात लिहिली जात. अशा स्थितीत चित्रांशिवाय लिहिलेलं वर्णन समजणं सोपं नव्हतं; म्हणून "टीकां'च्या माध्यमातून लेखक स्वतः (किंवा अन्य टीकाकार) श्लोकांचं विवेचन करत. अशा टीकेत आधुनिक गणितात वापरतात, तशा आकृत्या आणि उदाहरणं वापरून लेखनाचा अर्थ विशद केला जात असे. "गोलाध्याया'तसुद्धा ही पद्धत दिसते.

"गोलाध्याय'मधलं एक प्रकरण सर्वस्वी यंत्रांना, म्हणजे निरीक्षणाच्या उपकरणांना, वाहिलेलं आहे. त्यात काल मोजणारी उपकरणं आहेत. चक्रयंत्र, अर्धचापयंत्र, तुरीययंत्र, फलकयंत्र, यष्टियंत्र आदींची चर्चा पाहून भास्कराचार्य प्रत्यक्ष निरीक्षणांनादेखील महत्त्व देत असे, याची जाणीव होते. ही यंत्रं कशी बनवायची आणि कशी वापरायची, याची चर्चा या प्रकरणात आढळते.

"ग्रहणवासना' या अध्यायात ग्रहणांची चर्चा करताना सूर्यग्रहण आणि चंद्रग्रहण यांच्या स्पर्शदिशा आणि मोक्षदिशा कुठं असतात आणि का असतात, यांची कारणमीमांसा करण्यात आली आहे. सूर्यग्रहणात पश्चिम दिशेत स्पर्श तर पूर्वेत मोक्ष होतो, तर चंद्रग्रहणात याच्या उलट स्थिती असते. याची चर्चा करताना भास्कराचार्य राहू-केतूची संकल्पना खोडून काढतो; पण वेद-पुराण आदींमधल्या विश्वासांना तडा जाऊ नये म्हणून आपला निष्कर्ष अनाक्रमक शब्दांत व्यक्त करतो!

सूर्य ज्या मार्गानं जातो, ते क्रांतिवृत्त आणि त्यानं विषुववृत्ताशी केलेला कोन यांचा एक परिणाम म्हणजे दिवस आणि रात्र यांच्या कालखंडात फरक पडतो. त्यामुळं सूर्य विषुववृत्ताच्या उत्तरेला असला तर उत्तर गोलार्धात रात्रीपेक्षा दिवस लांब, तर दक्षिण गोलार्धात

त्याउलट स्थिती असते. त्रिकोणमितीनं या गोष्टीचा उलगडा होऊ शकतो, हे भास्कराचार्यानं दाखवून दिलं आहे.

याचाच परिणाम म्हणून 66 अंश अक्षांशाच्या उत्तरेला काही काळ मध्यरात्री आकाशात सूर्य दिसतो (उन्हाळी महिन्यात), तर असाही काळ असतो, की जेव्हा दिवस सूर्यदर्शनाशिवाय जातो (थंडीच्या मोसमात). याचं कारणही वरील गणिताद्वारे देता येतं, हे भास्कराचार्य समजावून सांगतो. भास्कराचा पिंड शिक्षकाचा आहे, याची जाणीव "गोलाध्याय' वाचताना पदोपदी होते. कारण, ठिकठिकाणी त्यानं प्रश्न पेरले आहेत व उत्तरं दिली आहेत. शेवटचा "प्रश्नाध्याय' तर प्रश्नांनीच व्यापलेला आहे. मला वाटतं, की त्याची ही पद्धत आधुनिक गणित आणि विज्ञान यांना वाहिलेल्या पाठ्यपुस्तकांनी वापरण्याजोगी आहे.

भास्कराचार्याचं गणितावरचं कार्यही प्रगल्भ आहे. "लीलावती' या ग्रंथात भूमिती, बीजगणित व अंकगणिताचा सुंदर संगम दिसतो. अशा विषयांवर आधारित गणितं मनोरंजक आहेत.

एक उदाहरण पाहा ः मधमाश्यांच्या समूहाच्या निम्म्या संख्येच्या वर्गमुळाइतक्या संख्येनं एक थवा मालती वृक्षाकडं गेला. त्यांच्या पाठोपाठ एकूण संख्येच्या आठ नवमांश माशाही तिकडं गेल्या. एक नरमाशी कमळाच्या बंद पाकळ्यांत अडकून पडली, तर फुलाबाहेर तिची जोडीदार तिच्या आवाजाला प्रतिसाद देत उडत होती...तर मुली, सांग एकंदर किती माश्या होत्या?

(भास्करानं हा ग्रंथ गणितात हुशार असलेल्या आपल्या कन्येला - लीलावती हिला - उद्देशून लिहिला होता, असा एक समज आहे).

भास्करानं अनेक गणिती शोध लावले. चक्रवाल पद्धत वापरून त्यानं विशिष्ट प्रकारची गणिती समीकरणं सोडवून दाखवली. उदाहरणार्थ ः 61x2 + 1 = y2 हे पूर्णांक x, y साठी कसे सोडवणार, हा प्रश्न 1657 मध्ये फर्मा नावाच्या फ्रेंच गणितज्ञानं उपस्थित केला होता. अनेकांनी प्रयत्न केले आणि अखेर 1732 मध्ये ऑयलर या प्रख्यात गणितज्ञानं तो सोडवला; पण अलीकडं असं लक्षात आलं आहे, की हा प्रश्न भास्कराचार्यानं 1150 मध्येच सोडवला होता! चक्रवाल पद्धत वापरून त्यानं काढलेलं उत्तर ः

x = 226153980, y = 1766319049

या उदाहरणातून भास्कराच्या कर्तृत्वाची कल्पना येते.

------------#satishmarji#-------------------

English Translation :-

India has a great tradition in astronomy and mathematics from Aryabhata to Bhaskaracharya. Many such scholars passed away in India from the 5th century to the 11th century. The last gem in this series of scholars is Bhaskaracharya II. His 900th birthday came last month. This is the introduction of Bhaskaracharya's work for him ...

The tradition of Indian astronomy and mathematics dates back to Aryabhata (fifth century) and extends to Bhaskaracharya II (1114-1185). It would not be an exaggeration to call this period, which nurtures unbroken tradition, the Golden Age of India. India was, of course, at the forefront of mathematics and science at that time, compared to its neighbors or Europe in the far west. Translations of books written by Indian scholars were published by enthusiastic scholars in Arabia, and Indian knowledge became known elsewhere.

Some of the shining beads in this series of scholars were: Aryabhata (1) - Latdev - Brahmagupta - Bhaskar (1) - Lalla - Aryabhata (2) - Sripati - Bhaskar (2).

The last gem in this necklace is Bhaskar (2) or the one we know as Bhaskaracharya! After Bhaskaracharya, mathematical research continued in India, mainly in Kerala; But until recently, the significance of those discoveries was not fully understood. This is an attempt to give a brief overview of Bhaskaracharya's work on the occasion of his 900th birth anniversary in January 2014.

Bhaskara's birthplace should have been Patangavi, southwest of Chalisgaon in Jalgaon district (but there is no consensus among experts).

Bhaskara's large book "Siddhantashiromani" is in four parts; but each part can be said to be a separate book. The names of those four parts are: 1) Lilavati (Pati Ganita), 2) Algebra, 3) Grahaganitadhyaya and 4) Goladhyaya.

There are 4,346 verses in the volume "Grahaganitadhyaya", which contains the mathematics of the planets and the almanac. Solved this way.

To further explain Grahaganitadhyaya, he wrote the fourth book, Goladhyaya. It contains 2,100 verses. The book was widely circulated and translated into various countries. Bhaskaracharya is famous for his achievements in astronomy and how important that achievement was when one reads "Goladhyaya" comes to mind.

Bhaskaracharya has shown his sense of humor at the very beginning of "Grahaganitadhyaya".

Bhaskaracharya discusses why it is important for mathematics and astronomy to come together at the beginning of his book Goladhyaya. , Then he will be known as a "fool".

Bhaskar has started his discussion with such an introduction. In the beginning, he said that "the earth is round and the people of the southern hemisphere are standing in opposite directions (up and down)." The earth itself is surrounded by seven spherical layers of air. The names of these seven layers are: 1) geosphere, 2) flow, 3). Udvahasanjnaka, 4) Samvahasanjaka, 5) Suvahasanjaka, 6) Parivahasangka, 7) Paravahasangka.

According to modern information, the various layers of the Earth's atmosphere are determined. Of course, Bhaskara did not discuss on what basis he got the above information; He also concluded (from most of the Puranic descriptions) that water clouds, lightning, rainbows, Gandharvanagari and various colorful objects can be found at an altitude of about 100 km above the ground.

But one thing is clear from this preliminary discussion. Basically, the things that travel in the sky like earth, other planets, sun etc. have survived on their own dimness For example: Earth! If the earth is placed on four giants as previously thought, then what are those elephants standing on? A tortoise under an elephant, but under a tortoise? Instead of getting bogged down in such arguments, Bhaskara has chosen a different path.

According to the Buddhist philosophy of the time, the earth was considered to be constantly "falling" in the sky. Contradicting this view, Bhaskar gave the example of a rock falling on the earth, stating that "the earth is fixed in one place in the sky. Bhaskaracharya posed the question of how a rock can reach the earth as the speed of falling of the earth is much higher than the speed of falling of a stone "down". According to him, the earth attracts the stone, so the stone falls on the earth;

In this regard, there is an opinion that the origin of the theory of gravity should be attributed to Bhaskaracharya. Let's take a brief look at it here. Newton's conclusion about the gravity of the earth as the apple fell, is not the same conclusion reached by Bhaskar here, so far we can consider both the examples to be of the same level; But Newton discovered the law of real gravitational inverse, by mathematically analyzing Kepler's laws of planetary motion. For this he used his own new branch of mathematics, Calculus; So Newton is credited with the law of gravity, that's right. Such a mathematical interpretation is not found in the works of Bhaskara or any other Indian thinker.

However, the main focus of "Goladhyaya" is on the mathematics used to observe planets and stars in the sky. Questions like where to find such planets or stars if observed from a certain latitude and longitude are solved here. Geometry and spherical trigonometry are used for this. The subject was older than calculus and therefore familiar to most mathematicians.

At that time books were being written in verse Sanskrit. In such a situation, it was not easy to understand the description written without pictures; Therefore, the author himself (or other commentators) used to interpret the verses through "Tikas". Such tikas are used in modern mathematics to explain the meaning of writing using such figures and examples. This method is also seen in "Goladhyaya".

One of the chapters in "Goladhyaya" is devoted to all instruments, the instruments of observation, which include the measuring instruments of yesterday. A discussion of how to use it is found in this case.

While discussing eclipses in the chapter 'Eclipse Lust', the causality of the eclipses and lunar eclipses has been explained as to where and why the eclipses are in the eclipse. Let's erase the concept; but let's break the beliefs in Veda-Purana etc. They therefore concluded anakramaka his words!

One of the effects of the ecliptic and the angle it makes with the equator is the difference in the duration of day and night. So if the sun is north of the equator, the day is longer than night in the northern hemisphere, and longer in the southern hemisphere.

The opposite is the case. Bhaskaracharya has shown that trigonometry can explain this.

As a result, the sun appears in the midnight sky (summer months) for some time north of 66 degrees latitude, while there is a time when the day passes without sunlight (in the cold season). Bhaskaracharya explains that the reason for this can also be given by the above mathematics.

Bhaskara's body belongs to the teacher, he realizes step by step while reading "Goladhyaya" because, in some places, he has sown questions and given answers. The last "Prashnadhyaya" is occupied with questions. I think his method is useful for textbooks devoted to modern mathematics and science.

Bhaskaracharya's work on mathematics is also profound. The book "Lilavati" shows a beautiful confluence of geometry, algebra and arithmetic. Mathematics based on such subjects is interesting.

Consider an example: a swarm of bees, half the number of square roots, went to the Malati tree. They were followed by eight-ninths of the total number of fish. A gentleman was caught in the closed petals of a lotus, while her mate was flying outside the flower in response to her voice ... So girls, tell me, how many fish were there?

(It is believed that Bhaskara wrote this book for his daughter who is well versed in mathematics - Lilavati).

Bhaskara made many mathematical discoveries. Using the Chakraval method, he solved certain types of mathematical equations. For example: The question of how to solve the integer 61x2 + 1 = y2 for x, y was posed in 1657 by a French mathematician named Ferma. Many tried and finally in 1732 the famous mathematician Euler solved it; But recently it has been noticed that this question was solved by Bhaskaracharya in 1150! The answer he drew using the Chakrawal method:

x = 226153980, y = 1766319049

This example gives an idea of Bhaskara's work.

Comments

Post a Comment

If you have any doubt, please let me know.